Salt is In All Types of Food. Here’s How to Cut Your Daily Sodium Intake

How to Cut Your Daily Sodium Intake, While this guidance is voluntary, its goal is to reduce the average daily sodium intake by about 12 per cent — from the 3,400 mg that people in the United States typically get to 3,000 mg — over the next 2½ years. While that’s still more than the recommended threshold of 2,300 mg, it’s a step in the right direction, says Anne Thorndike, an associate professor of medicine at the Harvard Medical School and volunteer chair of the American Heart Association’s Nutrition Committee.

Much of the sodium that people take in — over 70 per cent — comes from packaged and processed foods and restaurant meals. So if many companies follow these guidelines, it could have a significant effect on heart health, Thorndike says.

Issues with Salt

Despite what you may have heard about sodium getting an unfair shake, a majority of evidence shows that cutting back protects your health.

That’s because eating too much can increase blood volume, elevating blood pressure and forcing your heart to work harder, says Julia Zumpano of the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Human Nutrition. That raises the risk for stroke and heart disease.

A study published in 2014 by Tufts University in Boston showed that 1 in 10 cardiovascular-related deaths worldwide is at least in part due to a high-sodium diet. And according to a study of more than 10,000 people published in 2021 in the New England Journal of Medicine, every 1,000 mg of sodium excreted in urine (which represents intake) increases cardiovascular disease risk by 18 per cent.

Shake It Off

That said, finding a balance between less salt and tasty food can be tricky. Salt has a unique taste that’s hard to mimic, says Carolyn F. Ross, a professor of food science at Washington State University in Pullman.

What’s more, sodium is found in foods where you might not expect it, such as cereal and bread. These expert tips can help you reduce your daily sodium intake.

• Take a tally. “Write down how much sodium you’re getting from foods throughout the day,” Zumpano suggests. This allows you to spot the top culprits and choose where to cut back. You might decide, for instance, that you can’t sacrifice salting your eggs but you’re okay snacking on unsalted almonds (0 mg of sodium per ounce) instead of pretzels (about 350 mg of sodium per ounce) or opting for reduced-sodium soy sauce.

• Train your taste buds. According to the FDA, people typically don’t notice small reductions — about 10 percent — in sodium. Sprinkle a little less salt onto every meal, and gradually lower that amount even more. Over time, your tastes and preferences can change, so you won’t need as much salt to feel satisfied, Ross says.

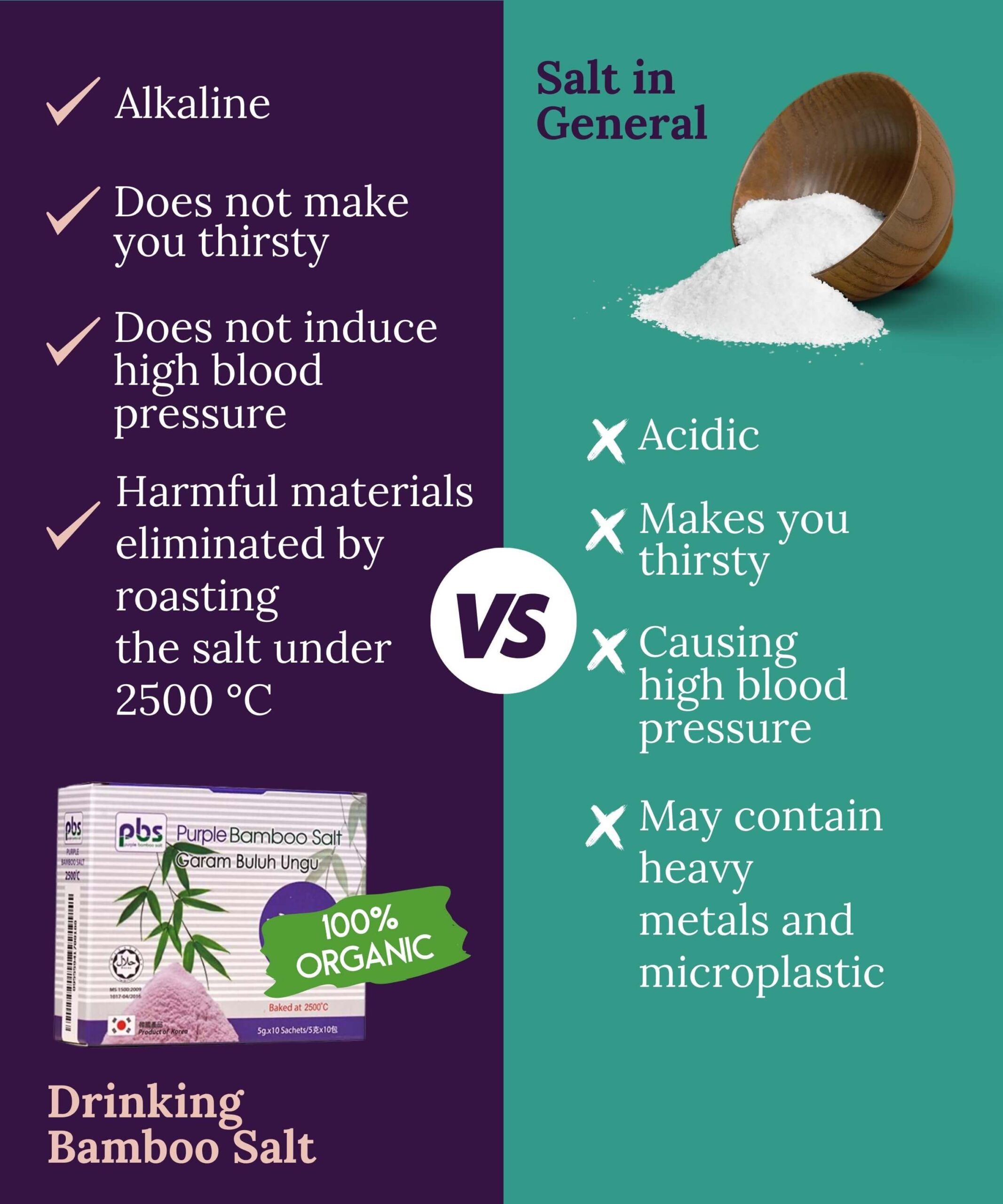

• Upgrade your salt. Ounce for ounce, table, kosher and sea salt have about the same sodium count. But the last two often have larger crystals that take up more volume on a measuring spoon, so you wind up getting less sodium in recipes. Another smart move: Use a salt shaker with smaller holes. That slows the flow so you’ll use less salt overall, Ross says. The most recommended would be to change your salt to Bamboo Salt. Bamboo Salt is the right salt. Bamboo salt is produced at high temperatures and hence the particles are small which help to get absorbed in the body along with the minerals.

• Swap in salt substitutes. These products add either saltiness or enough of a savoury flavour called umami so you don’t miss the salt. In a 2021 New England Journal of Medicine study of almost 21,000 older adults with hypertension or a history of stroke, half used a substitute made from 75 per cent salt and 25 per cent potassium chloride. After about five years, those who cooked and seasoned with the substitute were 13 to 14 per cent less likely to have a heart attack or stroke compared with those who used salt. As for taste, check out the results of a blind taste test of six popular salt substitutes by a Consumer Reports panel of sensory experts.

• Skip salt as you cook. Salt gets incorporated into the food, which means you might not taste it that much in the final product, Ross says. Instead, sprinkle it on right before serving. When you add it at the end, the crystals rest on top of the food. The salt hits your tongue, so you’re better able to taste it — and won’t need as much.

• Perk up food with spices, herbs and aromatics. They add flavour and disease-fighting antioxidants with little sodium, Zumpano says. According to research published in 2015 in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, people who cooked with herbs and spices significantly reduced their daily sodium intake. Experiment with garlic, onion, fresh and dried herbs, and seasoning blends. “In recipes, you can replace a half or full teaspoon of salt with a herb blend,” Ross says. An acid, such as lemon juice or vinegar, can also brighten the flavour of a dish.

• Spot hidden sodium sources. Manufacturers add sodium to the food you might not expect it to be in to enhance flavours and textures and act as a preservative. “The sodium in processed and packaged foods can really add up throughout the day,” Thorndike says. A slice of bread, for instance, can have 240 mg or about 10 per cent of the recommended daily sodium intake. Certain cereals deliver more than 300 mg in a serving, and pasta sauces contain upward of 500 mg per half-cup. When grocery shopping, check labels to see how much sodium an item is packing.

• Decode claims. “Light in sodium” means a product has at least 50 per cent less than its original or a competing one, while “reduced sodium” means it has at least 25 per cent less. But even with the reduction, the sodium content can still be high, Zumpano says. Better options: Low sodium (140 mg or less per serving), very low sodium (35 mg or less), sodium-free (less than 5 mg) and no salt added (no salt, but not necessarily a low-sodium food).

For more advice please feel free to write to us at hello@yourpurplelife.com